FINDING HOME - Bosnia-Herzegovina

SURVIVORS - Spain

RAZOR WIRE - Serbia

TIME PASSES DIFFERENTLY - Hungary

IT IS INCREDIBLY QUIET HERE - Ukrainian exodus

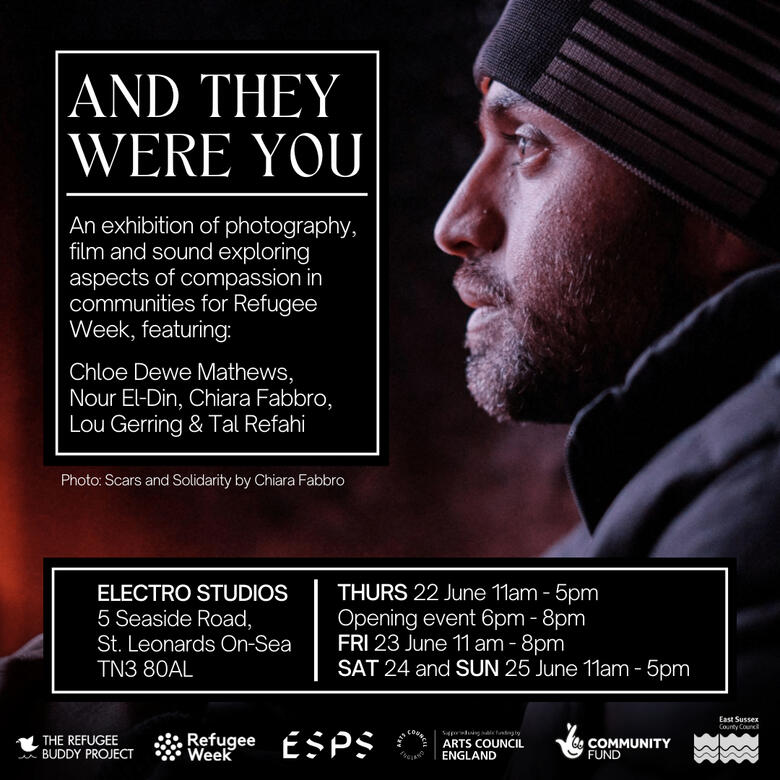

SCARS AND SOLIDARITY - Bosnia-Herzegovina

INVISIBLE BORDER - Greece

LIFE IN LIMBO - Malaysia

·

DEMONSTRATIONS - United Kingdom

·

STOLEN MOMENTS

You can order a fine art print by selecting the photo of your choice.

To request any other photo or format, just send me an email at [email protected].You can also support my work through a one-time donation here.

Thank you!

Lakes of Fusine, Italy

30x20cm

Fine art print on Canon Deep Matte paper, with a smooth finish.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£30

30x20cm, board mounted

Fine art print on Mohawk Eggshell paper, mounted onto a rigid board.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£40

To request another photo or format, send me an email at [email protected].

Gran Canaria, Spain

30x20cm

Fine art print on Canon Deep Matte paper, with a smooth finish.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£30

30x20cm, board mounted

Fine art print on Mohawk Eggshell paper, mounted onto a rigid board.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£40

To request another photo or format, send me an email at [email protected].

Gran Canaria, Spain

30x20cm

Fine art print on Canon Deep Matte paper, with a smooth finish.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£30

30x20cm, board mounted

Fine art print on Mohawk Eggshell paper, mounted onto a rigid board.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£40

To request another photo or format, send me an email at [email protected].

Hangzhou, China

30x20cm

Fine art print on Canon Deep Matte paper, with a smooth finish.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£30

30x20cm, board mounted

Fine art print on Mohawk Eggshell paper, mounted onto a rigid board.Production: 5 business days + shipping time

£40

To request another photo or format, send me an email at [email protected].

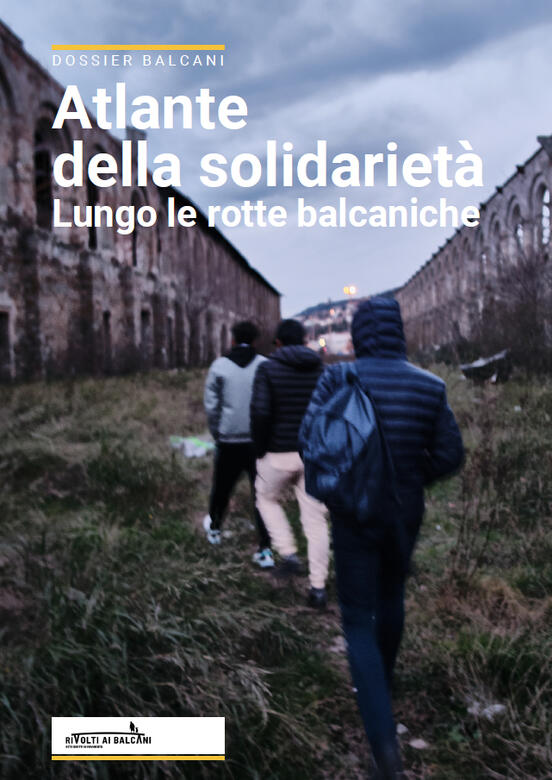

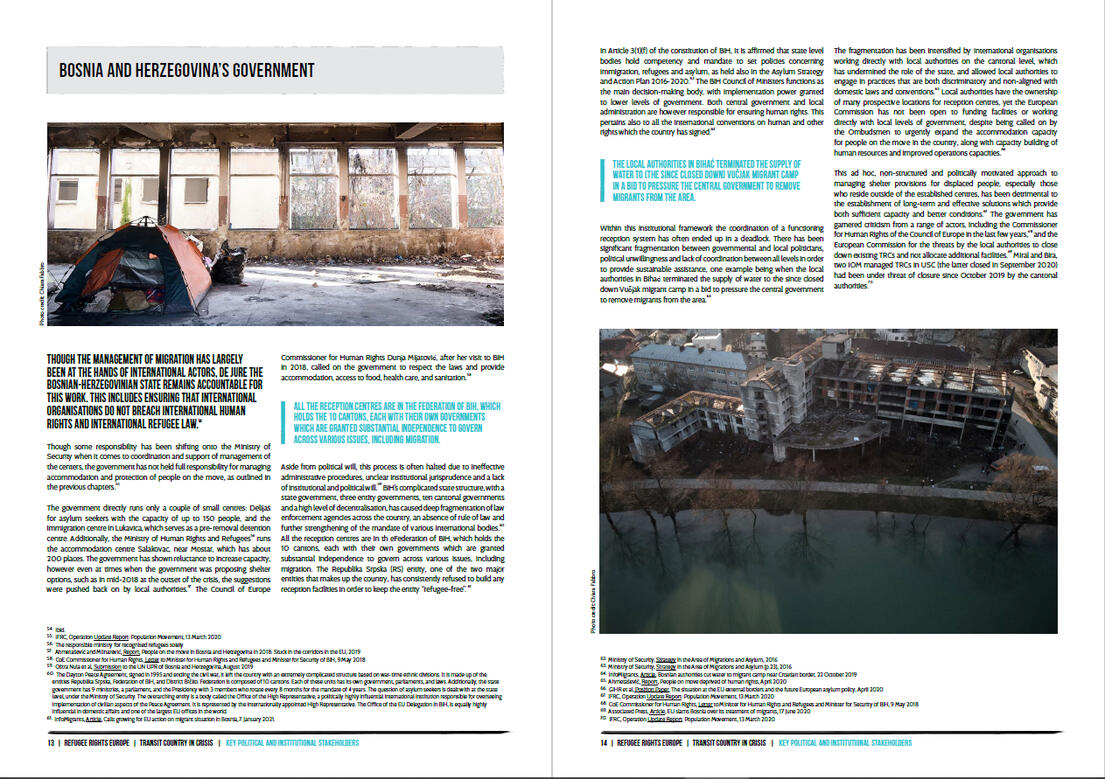

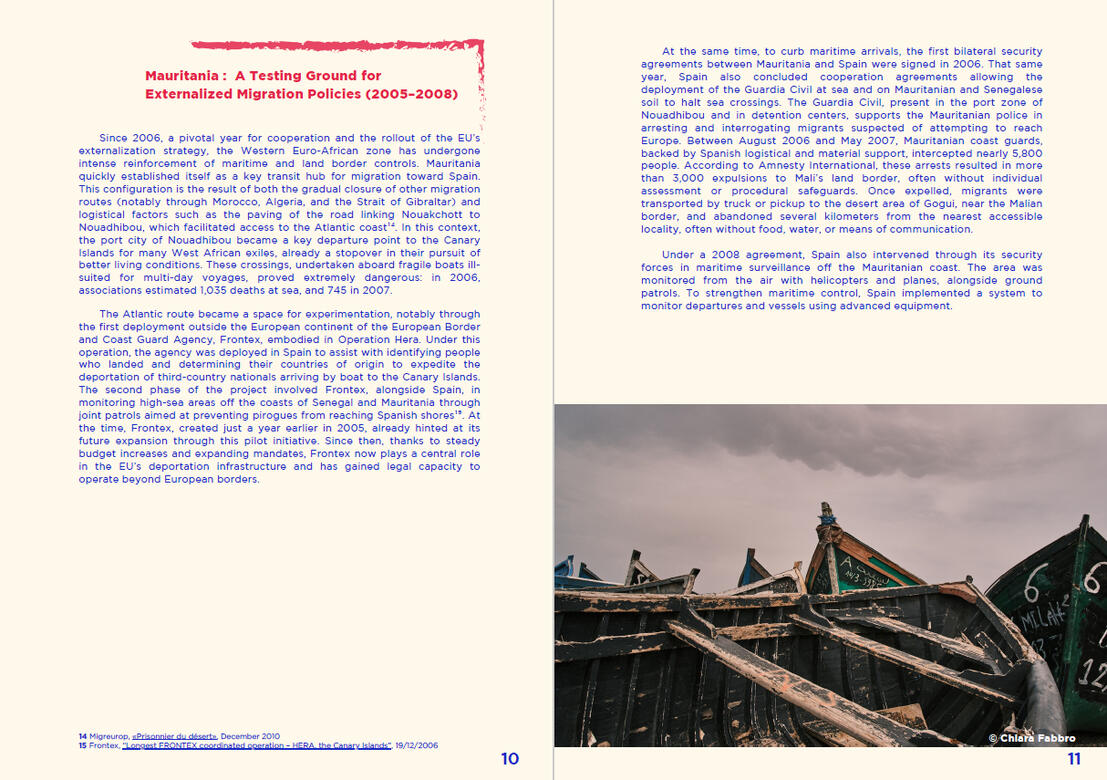

ALONG THE BORDER

Mostra fotografica

Bosnia-Erzegovina, Serbia, Italia

2021-2024

A chi ha condiviso con me un sorriso acceso dalla speranza o rubato alla stanchezza, alla rabbia o allo sconforto.A chi mi ha accolto con un ‘chai’ caldo, rigorosamente dolcissimo, e a chi, nel rigido inverno balcanico, ha insistito per lasciarmi un posto vicino al fuoco, pur sapendo che solo io sarei tornata in un appartamento riscaldato per la notte.A chi mi ha affidato un frammento della sua storia.

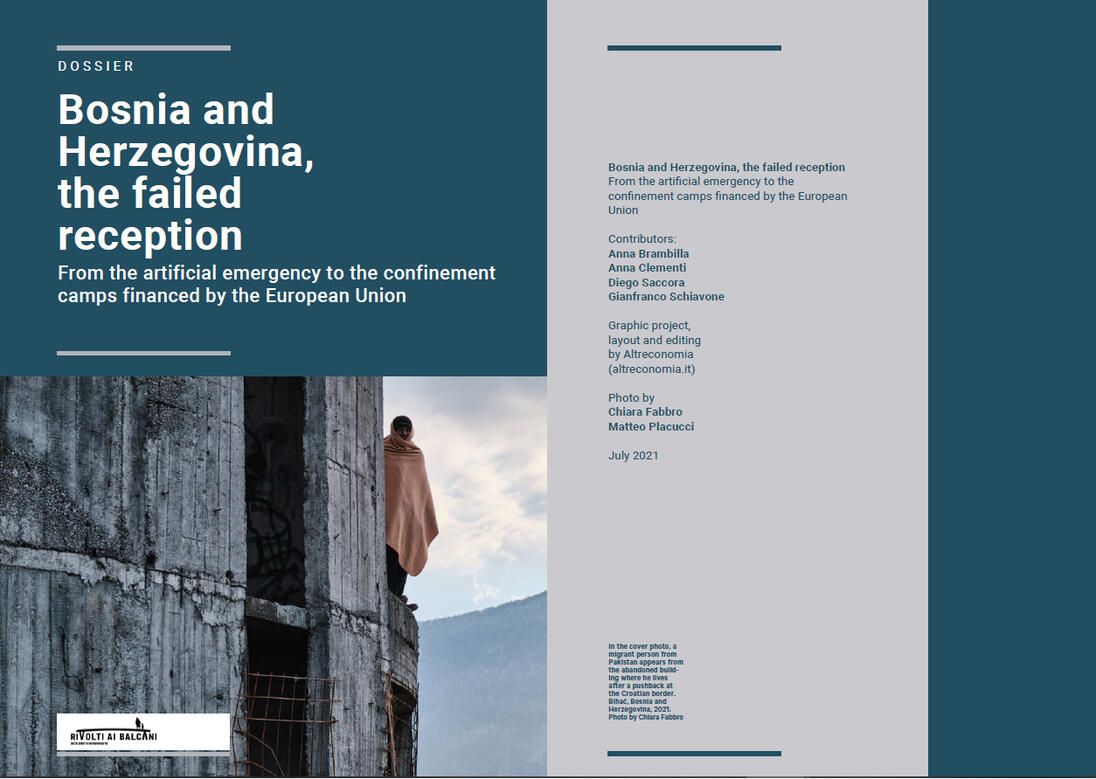

La fuliggine che annerisce i muri degli edifici abbandonati nei Balcani racconta delle vite in transito da questi luoghi. Persone che si sono lasciate alle spalle conflitti, persecuzioni o privazioni, e sono alla ricerca di una vita dignitosa in Europa. Durante il viaggio il fuoco diventa uno strumento di sopravvivenza fondamentale, per scaldarsi, cucinare e lavarsi.Uomini, donne e bambini provenienti da Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran o Siria, insieme ad altri paesi, non hanno altra scelta che pericolosi attraversamenti irregolari dei confini per poter raggiungere l’Europa. I sistemi di accoglienza ufficiali lungo la rotta balcanica offrono spesso condizioni del tutto inadeguate e non hanno sempre posti sufficienti per tutti. Si trovano inoltre lontano da quell’ambito confine che i ripetuti respingimenti alla frontiera trasformano in un game perverso, dove ci si gioca tutto e passare al livello successivo può richiedere mesi, se non addirittura anni.Le persone migranti trovano pertanto rifugio in edifici abbandonati o accampamenti informali vicino al confine, in condizioni di vita estreme. Luoghi dove il tempo è sospeso tra la vita che hanno lasciato e la speranza per un futuro migliore.Attraverso le mie foto ho voluto raccontare questo limbo ai margini e le storie di quelle “genti diverse venute dall’Est”, che forse così diverse non sono.

La mostra e il catalogo sono stati commissionati e prodotti dal Comune di Ravenna e dalla Rete contro le discriminazioni, nella cornice del Festival delle Culture 2024.

Contributo delle alunne e degli alunni delle classi 4D e 4E dell'Istituto Delfico di Montesilvano (Pescara):

ALONG THE BORDER

Catalogo fotografico

Bosnia-Erzegovina, Serbia, Italia

2021-2024

Un racconto fotografico dai confini lungo la rotta balcanica: vite sospese in un limbo ai margini e storie di “genti diverse venute dall’Est”, che forse così diverse non sono.

“Con scatti di grande potenza narrativa [...] ci racconta dell’indomita speranza e della resilienza di protagonisti tragici, in una sorta di epica dei diritti umani.”

Federica Moschini, Assessora all’Immigrazione del Comune di Ravenna

Il catalogo contiene 76 fotografie accompagnate da testi di Chiara Fabbro e citazioni delle persone protagoniste.Prefazione di Chiara Milan, Ricercatrice in Sociologia Politica della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa e premessa di Federica Moschini, Assessora all’Immigrazione del Comune di Ravenna. Nuova edizione con una premessa di Maurizio Fabbri, Presidente dell’Assemblea legislativa della Regione Emilia-Romagna.

Fotografie, testi e design grafico di Chiara Fabbro. Tutti i diritti riservati. Prodotto dal Comune di Ravenna e dalla Rete contro le discriminazioni della Regione Emilia-Romagna. Finito di stampare a Forlì nel mese di giugno 2024.Seconda edizione prodotta dall'Assemblea legislativa della Regione Emilia-Romagna. Finito di stampare a Bologna nel mese di marzo 2025.25 x 21 cm, 120 pagine, brossura a filo refe

ISBN 979-12-210-6428-5

FINDING HOME

Mostra fotografica

Bosnia-Erzegovina 2021Le vite sospese di donne, uomini e bambini lungo la "rotta balcanica"

"While yearning

for the motherland

we find home

between transits

and parking lots

of countries

which have never

heard our names."Elona Beqiraj

Sono migliaia le persone che ogni anno cercano di raggiungere l’Europa seguendo la "rotta balcanica". Vengono prevalentemente da Afghanistan e Pakistan, ma molti sono anche coloro che arrivano da altri Paesi, quali Iran, Iraq o Siria. Fuggono da conflitti, persecuzioni o privazioni e sono alla ricerca di una vita dignitosa. Da quando la rotta ha iniziato ad attraversare la Bosnia ed Erzegovina, nel 2018, il Paese è diventato per loro una fermata obbligata. Uomini, donne e bambini vengono infatti regolarmente respinti quando cercano di attraversare il confine con la Croazia, nel cosiddetto “game”. Sono frequenti i resoconti di respingimenti violenti e la maggior parte delle persone riferisce di aver tentato il “game” molteplici volte. Costretti a vivere per mesi, a volte persino anni, nei corridoi freddi e anneriti degli edifici abbandonati e negli accampamenti di fortuna, in un limbo dove il tempo sembra essersi congelato.

La mostra è stata commissionata e prodotta dal Consorzio Italiano di Solidarietà, per la rassegna 'Rotte di migrazioni forzate, di diritti e di cittadinanza'.

Print and online press

Interviews

NGOs

RiVolti ai Balcani

RiVolti ai Balcani

RiVolti ai Balcani

Asylum Seekers Drop in Centre

Govend London

S/PAESATI

RiVolti ai Balcani

The Refugee Buddy Project

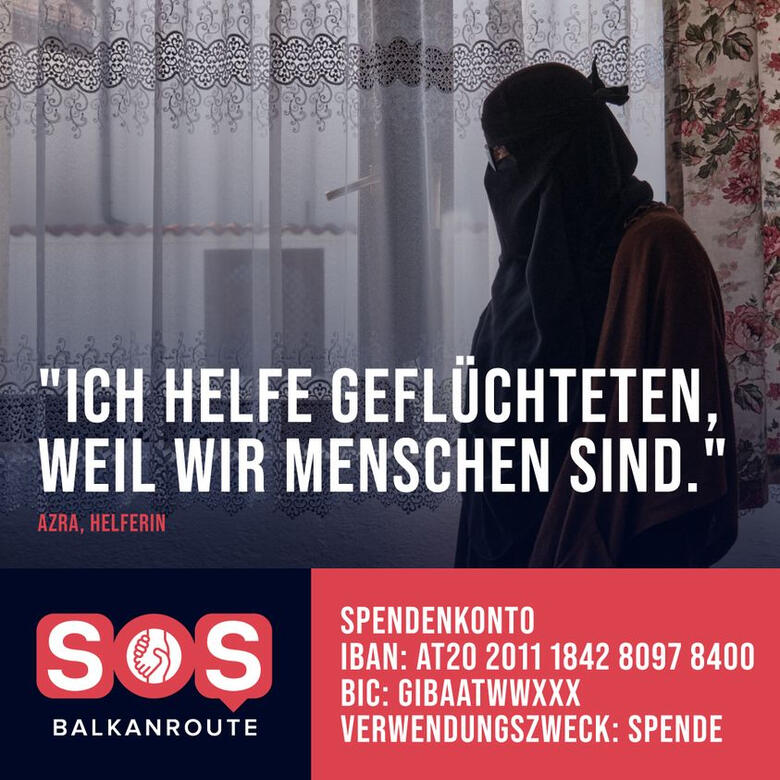

SOS Balkanroute

RiVolti ai Balcani

RiVolti ai Balcani

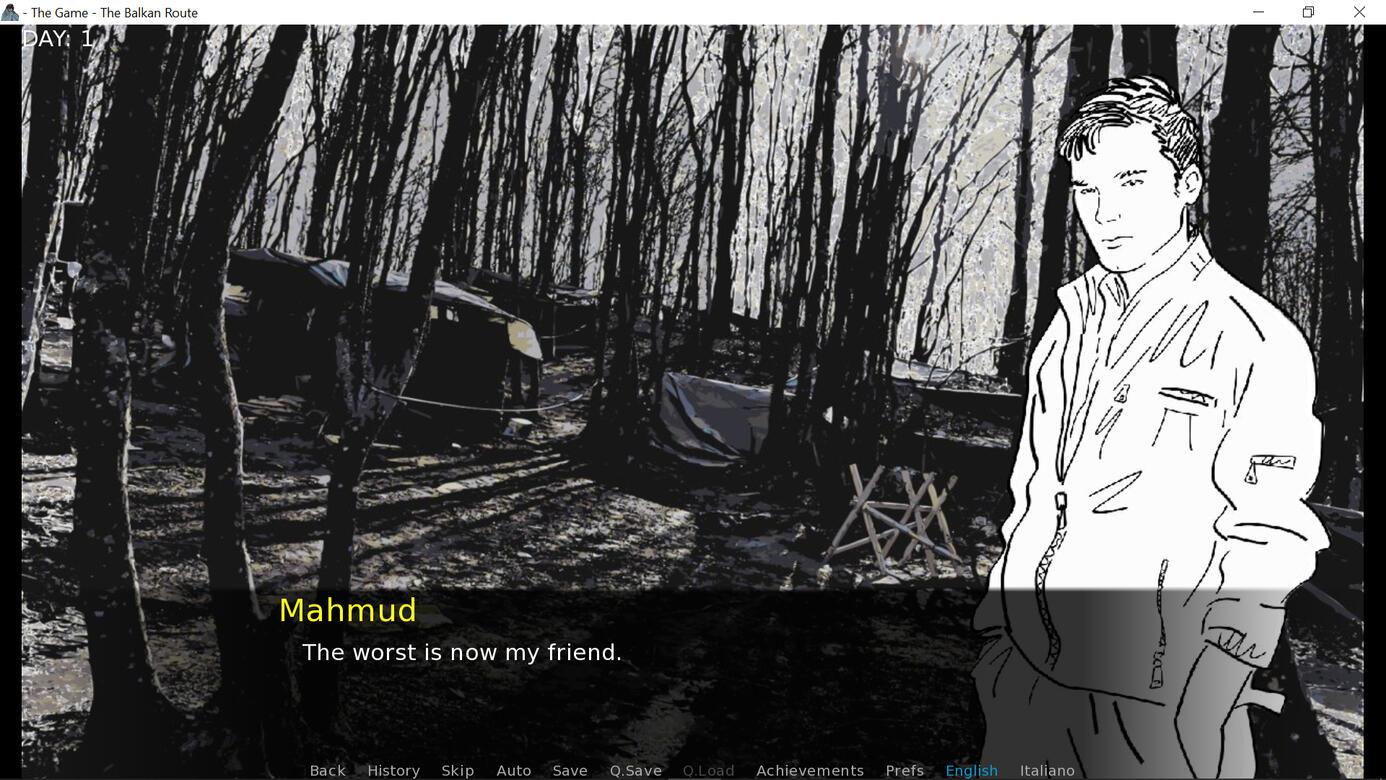

Dialobot - Visual novel

Refugee Rights Europe

Consorzio Italiano di Solidarietà

Europe Must Act

Specto Media

Leave No One Behind

Refugee Rights Europe

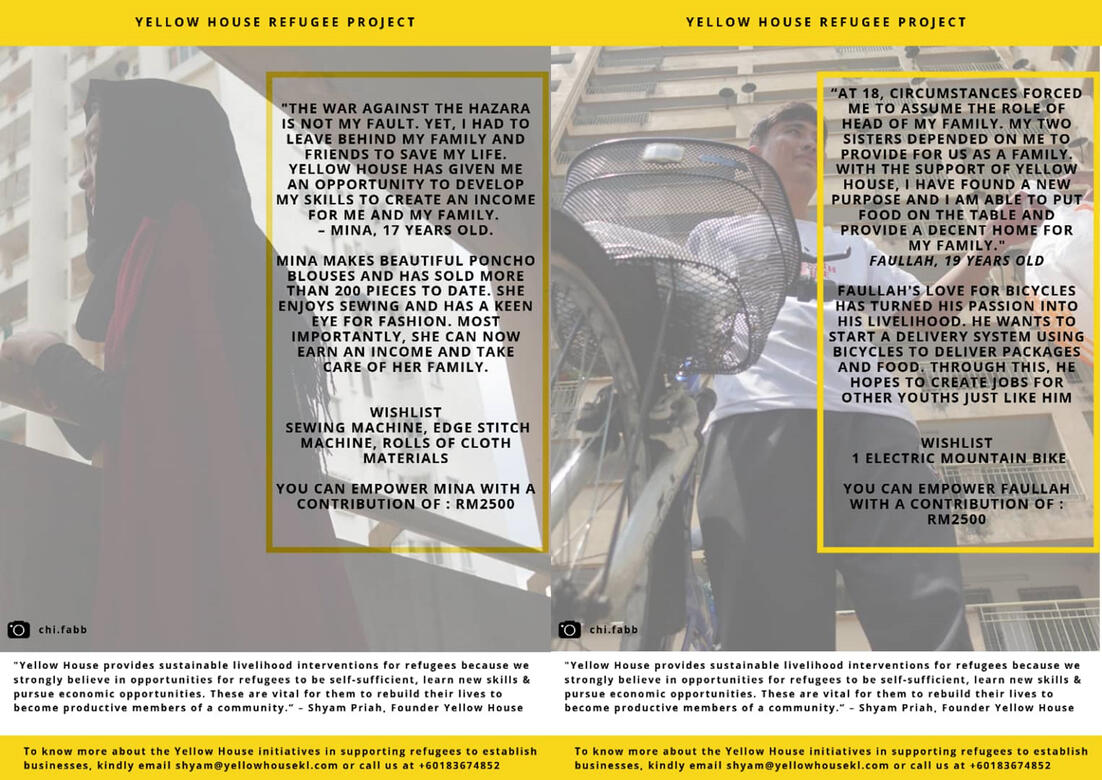

Yellow House Kuala Lumpur

Dealing with anger through art therapy

Centre for Syrian refugee children with PTSD

Amman, Jordan

© Ben Owen-Browne

I am an Italian documentary photographer based in London focusing on social issues.I have a fascination with people's life stories and the warmth of human connections. I love exploring what makes us so different yet so similar, across cultures and life journeys, and the familiar within our incoherent world.I have worked in a variety of places, from the suburbs of Kuala Lumpur, in Malaysia, where those who have fled conflict and persecution cannot be granted refugee status and are forced into a life in limbo; to the squats in the Balkans where migrant men, women and children get stuck during their journey towards Europe; to the beaches of the Canary Islands, the destination for thousands of people who every year set off in flimsy boats from the coast of West Africa, facing what is probably the most dangerous journey into Europe.My work has been published in a range of print and online magazines and newspapers such as Al Jazeera English, Balkan Insight, Altreconomia, Solomon and El Salto. I have been commissioned by Refugee Rights Europe, RiVolti ai Balcani and several other NGOs. My photography has won the 2021 Portrait of Humanity award and received an honourable mention in Photography 4 Humanity Global Prize 2020, supported by the UN Human Rights Office. In 2022 I was shortlisted for the Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage Award and in 2022 and 2023 for the International Women in Photo Association Award. In 2025 I was selected for Earth Photo Award.In 2024 the Council of Ravenna and the Network against discriminations commissioned my exhibition and catalogue 'Along the border' for the Festival delle Culture, which was opened with Sebastião Salgado's exhibition on mass displacement 'Exodus'.

Awards

2025 EARTH PHOTO Award

2025 Der Greif curated Guest Room 'Sounds of Resistance'

2025 Zuma Press 'Pictures of the Month' for March

2023 International Women in Photo Association Award, Shortlisted

2023 Pride Photo Award

2022 Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage Award, Shortlisted

2022 International Women in Photo Association Award, Shortlisted

2022 Korridor – Innsbrucker Preis für Dokumentarfotografie, Pre-selection

2021 Portrait of Humanity

2021 Siena Creative Photo Awards, Shortlisted

2020 Photography 4 Humanity Global Prize, Honourable mention

2019 Reconstruction of Identities Open Call, FinalistExhibitions

2025 BredaPhoto Festival, 'Life stories' (Breda, Netherlands)

2025 EARTH PHOTO - Royal Geographical Society (London, UK)

2025 Amnesty International UK event, solo exhibition: 'Scars and Solidarity' (London, UK)

2025 Settimana della legalità e Giornata dell'Europa (Bologna, Italy)

2024 Festival delle Culture, solo exhibition and catalogue: 'Along the border' (Ravenna, Italy)

2023 Salusbury World event, solo exhibition: 'Scars and Solidarity' (London, UK)

2023 Rassegna 'Pace' (Modena, Italy)

2023 Festival S/paesati (Trieste, Italy)

2023 Migration Matters Festival, solo exhibition: 'Scars and Solidarity' (Sheffield, UK)

2023 The Refugee Buddy Project event, 'And They Were You' (Hastings, UK)

2023 PRIDE PHOTO, 'The Process of Change' (Amsterdam, Netherlands)

2022 Rassegna d'Arte Contemporanea Internazionale 'Espansioni' (Trieste, Italy)

2022 Rassegna 'Rotte', solo exhibition: 'Finding home' (Trieste, Italy)

2021 PHOTO International Festival of Photography (Melbourne, Australia)

2021 Belfast Photo Festival (Belfast, UK)

2021 Indian Photo Festival (Hyderabad, India)Features

2022 The Game, visual novel by Dialobot

2021 Portrait of Humanity Vol. 3, photographic book by HOXTON MINI PRESS

2020 Staying Home Together, photographic book by Exhibit Around - dotART and F-Stop MagazineScholarships

2023 'Effective reporting on migration' workshop, European Excellence Exchange in Journalism (Belgrade, Serbia)

2022 WPOW Annual seminar and portfolio review, Women Photojournalists of Washington

2022 'Arts for Justice' Residency, Ulex Project (Granada, Spain)

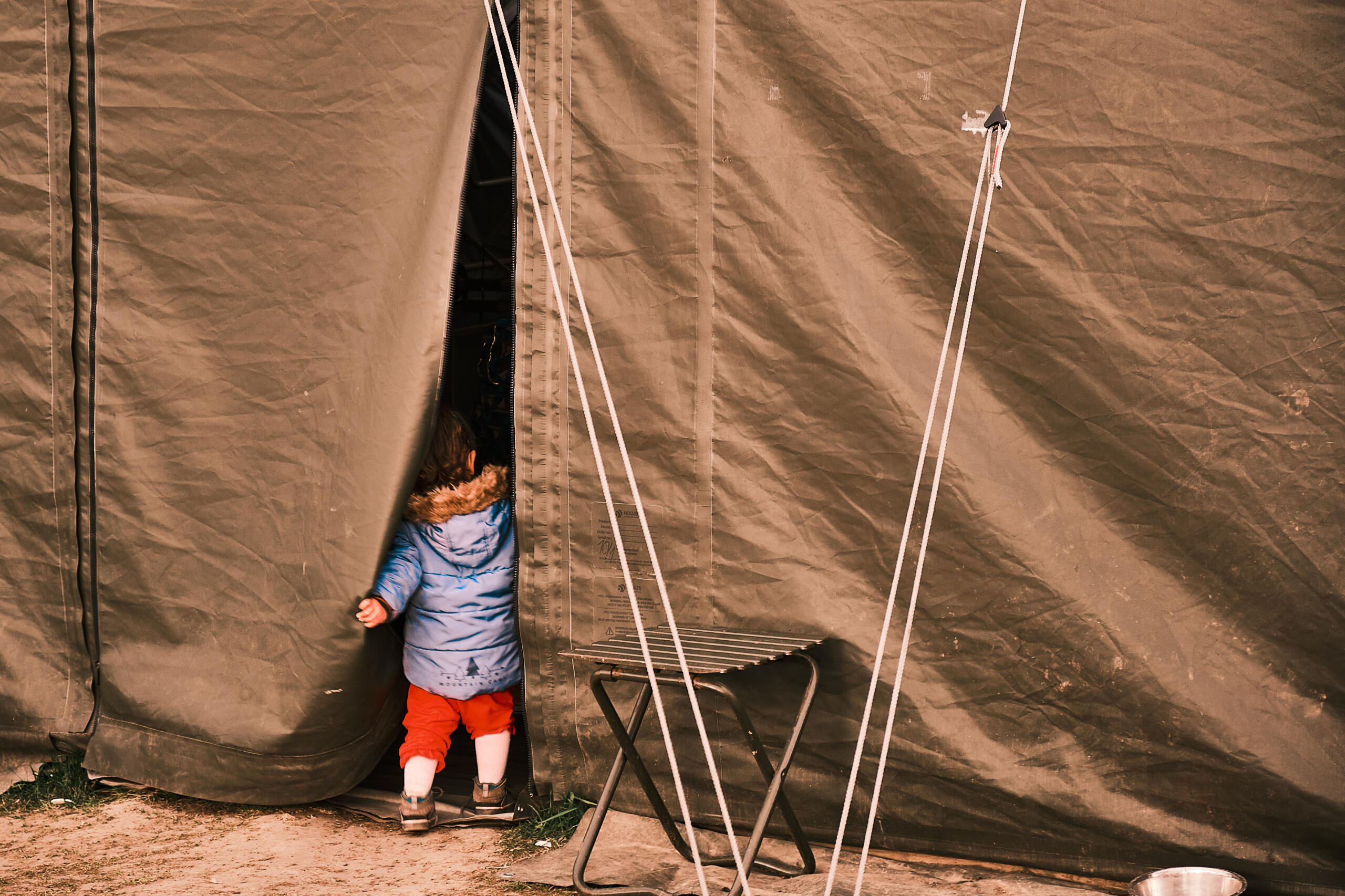

IT IS INCREDIBLY QUIET HERE

Testimonies and images from the Ukrainian war and exodus, 2022

A little girl entering an emergency tent at the border crossing of Vyšné Nemecké, Slovakia.

"War dismantled my life brick by brick. First, it took away the electricity and the Internet. Mobile communication and a generator became the most valuable resources. Money has generally lost its weight. Then the occupiers, about 70 tanks, drove into our village. They felled trees, destroyed playgrounds, shot into high-rise apartments, and into the windows of private houses. I will never forget the sound of the tank, like a tractor that came not to plow the land, but to destroy all living things." (Ruslan Biljakobich, Nemishajeve)"Already at the first roadblock, my children saw Ukrainian tanks moving through the streets of Irpin. There was no limit to their curiosity, because it was impossible to silence the roar of those iron cars. [...] Only women and children were allowed on the platform, so we said goodbye near the station building and my wife and children headed to the platform to the sounds of mines and shells exploding. [...] As soon as they walked in, the moment in my life that I hate more than anything came for me, waiting. Waiting and feeling like you can't do anything. Nobody knows if there will be a train, nobody knows if it will be able to pass, nobody knows what to do if it doesn't come. [...] And time dragged on." (Anonymous, Irpin)"All the cats were let out, the fish were fed, and the neighbours took the women and children out through the town of Stoyanka in the surviving cars. Everyone arrived safely. My friend and I were left alone. We walked through the destroyed city to the blown-up Romanov bridge. It was sad to look at the once flourishing and tidy city. Damaged cars, destroyed buildings and the last people left, mostly elderly - such a sad landscape. Now my friend and I are in Kyiv, we have moved into my apartment on Pechersk. It is incredibly quiet here, after six days of shelling. Maybe we'll get some sleep." (Anonymous, Irpin)"The explosion also damaged my house. Shrapnel pierced the wall of my father's room around his bed. By some miracle, he was not affected. "I don't want to be here" was my first thought. The evacuation was planned that same day. I packed my things in tears. My whole life fitted into a backpack with an embroidered patch. We planned to go to my aunt in Kyiv. Only 20 km from home, but as if on Mars. [...] The next day we were evacuated near the cultural centre. As if the Titanic was sinking, people were waiting for lifeboats. [...] After crossing the Zhytomyr highway, we were met by a Ukrainian block post and we all shed tears. War changes people. I will never be what I was." (Anonymous, Bucha)- Testimonies collected by Eleonora Kovalko during the first weeks of the Russian invasion.

Photos from the Ukrainian exodus in Hungary (Záhony, Beregsurány, Budapest) and Slovakia (Vyšné Nemecké, Michalovce), April 2022.

To read the story of Oksana and Iryna, who fled Ukraine with their children, go to TIME PASSES DIFFERENTLY.

TIME PASSES DIFFERENTLY

Hungary 2022

Sofiia, Oksana and Iryna just arrived from their hometown Ternivka, Ukraine, to the shelter in Záhony, Hungary.

Three-year-old Sofiia* was playing with a balloon in the corridor of the school, cluttered with boxes of donated clothes and supplies. One of the volunteers was offering tea from a makeshift cafe area. It was evening and the place was filled with a tired air. Only the little ones seemed to have energy, running through the classrooms that had been converted into temporary dorms - the bunk beds pushed against the blackboard, where someone had written “дякуемо”, Ukrainian for “Thank you”. This shelter in the border town of Zahony, in Hungary, had been set up to host the people who started arriving here from Ukraine since the evening of the 24th of February 2022. Zahony’s train station is the first stop after the border. People arriving here from Chop, the last stop in Ukraine, need to pass through border control before they can board a train bound for Budapest. If they arrive at night or need some rest, the emergency shelter is available, thanks to the mayor and volunteers from the community of Zahony.Among the people staying in the shelter, were Sofiia’s mum Oksana, 26, and Iryna, 32, with her children, aged 10 and 13, and their dog. They were exhausted after a 24-hour train journey from their hometown Ternivka, in East Ukraine. As the train was covering the vast distance to the border, they had been interrupted multiple times by air-raid sirens, leading to sudden halts in the middle of nowhere. “Sofiia was terrified by that loud sound,” explained Oksana. They would then sit in the darkness, wondering how long the wait would last and trying their best to keep calm, for the children - an extra challenge on an already difficult journey.Iryna and Oksana have been friends for many years. Both their husbands and Iryna were employed at the local coal mine, while Oksana used to work as a shop assistant. Back home, even though their city was not under direct attack, they were growing increasingly worried. Oksana’s husband was still working at the mine, whilst volunteering with anti-looting patrols and helping people who were fleeing. Iryna’s husband had already been drafted and was fighting on the frontline, 23 kilometres away from their home, and only able to communicate with his wife through short messages. "He cannot share any details", she explained. The noise and smoke from the bombings getting closer eventually made them decide to leave. They were worried, but tried to stay positive and think that it would all be over soon. “It will be just a bad memory, provided we all survive…” commented Iryna.Once in Zahony, some people would already have a specific destination in mind, maybe friends or family. Many others just fled without a plan, like Iryna and Oksana. “We don’t know where to go from here and we don’t have any connections," they explained. Beside the institutional support available, many people from all over Europe have gathered donations and opened their door to host those fleeing Ukraine. Iryna and Oksana were lucky enough to be offered to stay at Chris’s house. Chris and his wife had decided to make their lake Balaton holiday home available to Ukrainian refugees. “After the war started, I realised that some people needed our house more than we did,” said Chris, “I offered to help because I could.” When the first two families they hosted decided to go to Germany, Chris drove them to the train station. He then drove all the way to Zahony again, where local volunteers helped him find someone else happy to accept his offer. Thus his car, fully packed and the dog equipped with a nappy, left the border and headed west.After spending five weeks in Chris’s house, Iryna and Oksana felt that it was safe enough for them to return home. However the situation was far from easy. Despite it being quiet in Ternivka, they could hear explosions nearby. “Planes fly, sirens ring, it's scary“ explained Iryna. “There are a lot of refugees who are left without anything. There will be no everyday life until the war is over.” Iryna’s husband has more recently become directly involved in the fighting. “It’s very scary. It’s been almost two months, but time passes differently there,” said Oksana.*Names have been changed.

You can find this story in Balkan Insight and Altreconomia.

To see more images and read more testimonies from the Ukrainian war and exodus, visit IT IS INCREDIBLY QUIET HERE.

RAZOR WIRE

Serbia 2022

Graffiti on a wall in central Belgrade, Serbia.

Ibrahim* and Husam* were trying to reach Europe, but had been stuck on the Serbian side of the border for five months, as their attempts to cross had failed due to the pushbacks by the police. They had set up a small tent settlement near an abandoned factory, where many others were staying.Talking about the situation in his home country, Ibrahim shared a video from 2013 that had just been leaked. It showed blindfolded and handcuffed civilian men being told to run, before being shot by a regime intelligence officer, their bodies falling into a mass grave. “Three of my friends were killed in this way by ISIS,” explained Ibrahim.In 2011 Ibrahim was arrested in his home town of Homs. After the Friday prayer at the Mosque, his father had asked him to go buy some fish and he stopped to watch a protest against the regime, when the guards blocked the street and took almost everyone. There was no trial or official sentence. Ibrahim was just 14 years old. “The regime doesn’t care about your age, they just put you in prison,” he said. After a year, his father managed to get him out with a bribe, and he fled the country.On his journey out of Syria, in Idlib, Ibrahim met Husam. The two became friends and continued together, initially settling in Turkey. They lived in Izmir for nine years, doing all sorts of jobs. “We worked as tailors, blacksmiths, farmers, carpenters…you name it!” But conditions in Turkey are not easy for Syrian refugees. They are not granted refugee status according to the Geneva Convention but only temporary protection, which results in several limitations to their freedom of employment and movement within the country. They face heavy discrimination, as employers need to support their work permit application but have no incentive to do so. This leaves Syrians exposed to exploitation in the informal job market, preventing access to minimum wage and social security benefits. Moreover, in a country grappling with severe inflation, the climate is tense and racism is on the rise.Turkey is the country hosting the largest number of refugees worldwide, with over 3.5 million registered Syrians, but its attitude towards them is becoming increasingly harsh. Access to registration for temporary protection is severely limited and a growing number of Syrian refugees are being deported. “Turkish media lie, there is no safe place in Syria,” said Ibrahim, “Assad is still letting Russian forces conduct airstrikes.” Ibrahim and Husam applied to a resettlement scheme for the UK, but didn’t get accepted and thus decided to take matters into their own hands and come to Europe. “We want to reach a country that can give us an ID card,” concluded Ibrahim.The worst part of their journey, they said, was crossing from Turkey into Greece, due to the violent pushbacks by the police. They lost count of how many times they tried, but they think it was almost thirty. Their final, successful, attempt was also the most tragic one. It was a freezing cold night, they recalled, as they crossed the river Evros. There were three of them on the small rubber dinghy - Ibrahim, Husam and their friend Ali*. When they had almost reached the other side, the flimsy boat started to sink and they had to swim to shore. But Ali couldn’t swim. “It was dark and we couldn’t help him,” Ibrahim explained, almost justifying himself. Ali’s life was taken by the border.From Greece it took them a month to reach Northern Serbia. They decided to avoid going through Croatia, because of the renowned violence of its border police. “In Croatia they do what the Greeks do, they are brutal. We couldn’t stand any more heavy beatings, we have received enough in Greece,” said Ibrahim. They were now stuck at the Serbo-Hungarian border, along which runs a three-metre-high double fence, covered with razor wire. Its sharp blades can slice deep into flesh and are responsible for many of the injuries at this border. When people manage to cross, they are often detected by border police and returned to Serbia. After six failed attempts, Ibrahim and Husam ran into issues and lost all their money. They could no longer afford to pay the smugglers, who at the same time prevent people from attempting to cross by themselves.In the abandoned factory life was difficult. There is a state-run temporary reception centre in a nearby town but its conditions are squalid. “It’s overcrowded and skin disease is rife,” they said. Thus they preferred this makeshift accommodation. Ibrahim and Husam were sleeping in tents set up just outside the building, in the tall grass, and cooking on a fire pit built in a washing machine drum. They relied on the support of aid organisations visiting the squats on a regular basis, providing them with food, clothes, access to a camp shower once a week and basic medical care.On a day like any other, soon after the van from the independent organisation “No Name Kitchen” arrived, tea and biscuits materialised, along with dates. Music from a speaker livened up the atmosphere and Ibrahim and Husam broke into the traditional dance of Dabke, cheered by the other men. The group then joined in, including the European volunteers who tried to learn the basic steps - their attempts contributing to the cheerfulness of the moment.Ibrahim and Husam have since managed to reach Europe and have applied for asylum. Borrowing the money to complete the journey from friends and family was not easy and took time. The difficult circumstances forced them to split and they are now in two different countries but speak to each other every day. When asked about his hopes for the future, Ibrahim pondered for a little while before answering, “In Turkey refugees are accused of stealing jobs. I wish to find a country where people will not see us as a problem.”*Names have been changed.

You can find this story in Balkan Insight and Altreconomia.It was also part of my solo exhibition on the Balkan route 'Along the border', commissioned by the Council of Ravenna for the Festival delle Culture.

SCARS AND SOLIDARITY

Bosnia and Herzegovina 2021-2022

Azra, 62, is pointing at herself on an old photo. She is a Bosnian Muslim and fought during the Bosnian war, in the 90s, during which she lost many friends. She recollects that after the war many felt lost and turned to alcohol, drugs or even took their own lives. Azra wondered for a long time why she survived, she started rebuilding her family home, which had been bombed, and decided to devote her life to helping others.

"I know what it means to feel invisible," says Lejla. In 1992, at the beginning of the Bosnian war, she had to flee the country with her family. She recollects taking only one Barbie doll with her, but what was supposed to be just two weeks away from home turned into years of life as refugees. "Now I always make eye contact when I meet a migrant," explains Lejla, “they feel the same as me back then.”The people Lejla refers to, roaming the streets of Bihać, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in a temporary limbo, have fled wars, persecution or hardship and are faced with another challenge right on the doorstep of Europe. They are victims of regular and often violent pushbacks when they try to cross the border into Croatia.Official migrants reception centres often offer poor living conditions and are far from the border. Many of the makeshift shelters where migrant people are forced to live are near residential areas, and the reactions to their presence by the local communities are mixed. However, despite the complexity of the situation, in a country still dealing with its own scars, the examples of solidarity are not hard to come by.Asim is a Bosnian Muslim and was held in an internment camp during the war, from which his wife managed to free him through a prisoner exchange. Now his warm smile welcomes many of the migrant people in Bihać, where he has a small shop. "In this world we are all the same. There are some rotten apples," says Asim as he points to the fruit on display in his shop "but the majority of the people are good".Azra, a Bosnian Muslim woman, fought during the Bosnian war in the '90s. After the war finished, she wondered for a long time why she survived. She started rebuilding her family home, which had been bombed, and turned to religion, deciding to devote her life to helping others. Now she collects donations from the locals and distributes food and clothes to those in need, and she has soon become an important presence for many. “Sometimes I think I’m strong and that I can deal with all these emotions,” she says, “sometimes I just cry.”

You can find this story in Solomon as a longform and photo essay and in El Salto. It was shortlisted for the International Women in Photo Association Award and the Marilyn Stafford FotoReportage Award.'Scars and Solidarity' solo exhibition was produced by Migration Matters Festival (Sheffield, UK). It was also commissioned by Salusbury World (London, UK) and as part of the group exhibition 'And They Were You' (Hastings, UK). It was part of my wider solo exhibition on the Balkan route 'Along the border', commissioned by the Council of Ravenna for the Festival delle Culture.

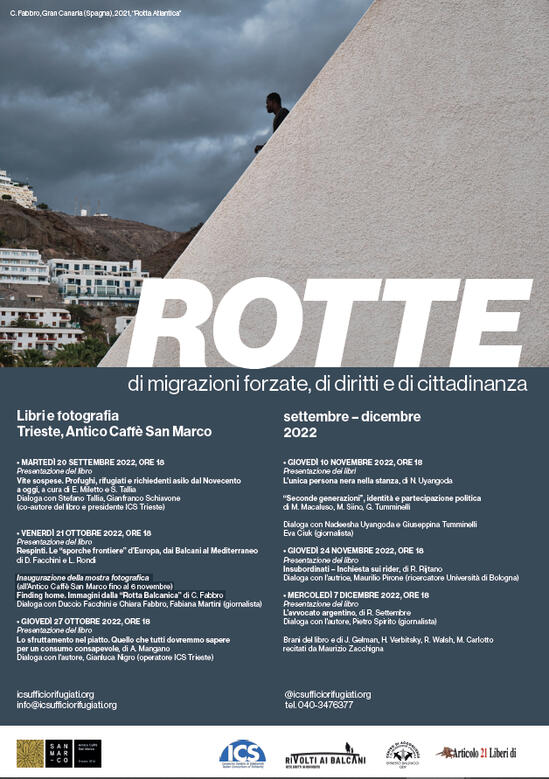

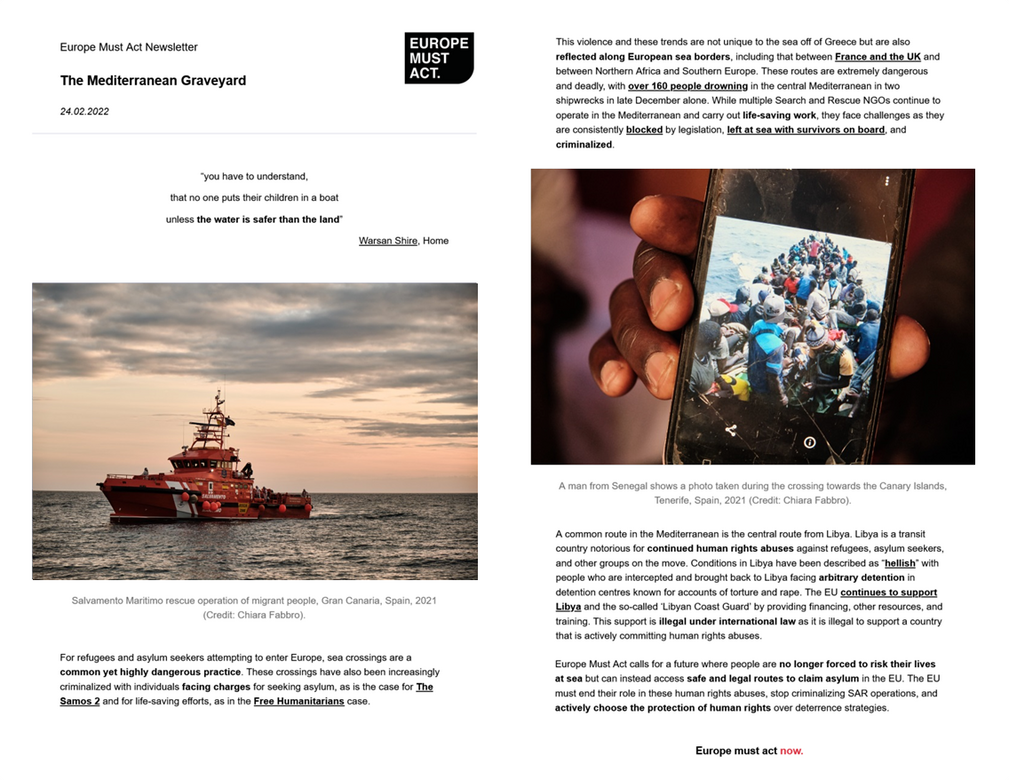

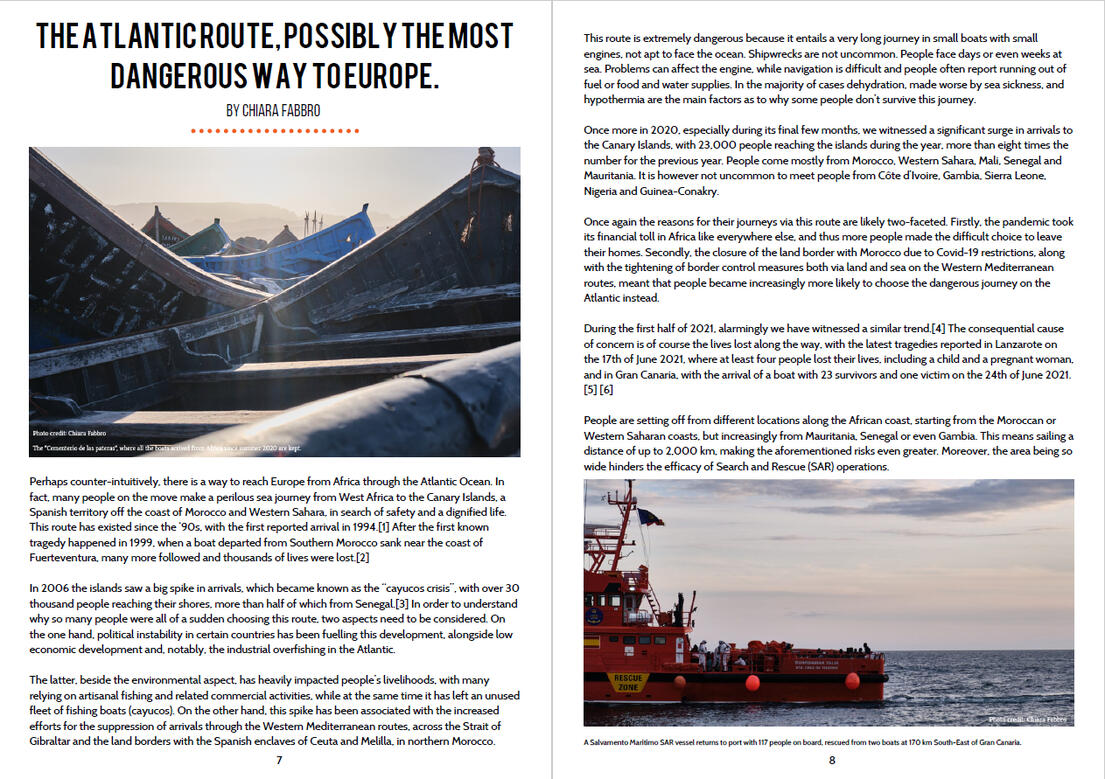

SURVIVORS

Canary Islands, Spain 2021

Spanish search and rescue vessel with 60 people from two separate boats onboard. The boats had been sighted by a yacht and a merchant vessel, respectively 67 and 5 kilometres south of Gran Canaria. This route requires sailing anywhere between 100 and 2,000 kilometres, depending on where the boats depart along the African coast. Such a wide area makes search and rescue missions extremely hard.

A young man from Senegal looks out at the horizon from the hotel where he is housed after reaching the Gran Canaria. At the end of 2020, several hotels left empty by the pandemic have been used to host migrants. While offering dignified accommodation for those who had endured so much, this also provided some financial relief to a suffering tourism industry. However, after objections by some in the local communities, the Spanish government transferred people to reception camps built ad-hoc.

“I wouldn’t face such a journey even with my 200 horse power engine” a Canarian fisherman said about people arriving from West Africa, on boats normally equipped with engines ten times less powerful.Tens of thousands of people, however, have been risking the arduous journey to Europe from Africa, through the rough waters of the Atlantic Ocean, to get to the Canary Islands, a Spanish territory off the western coast of Africa.Those who make this journey mostly come from Mali, which recently saw two military coups, Senegal, Morocco and Ivory Coast, among others. Besides the toll taken by the pandemic, West African economies based on artisanal fishing have been suffering more and more because of the ever-intensifying industrial fishing off their coasts, due to agreements with Europe and illegal activities by Chinese vessels. At the same time, the tightening of other routes to Europe forced people to search for alternative ways. This has been partially due to Covid-19 measures, but in big part as a result of European efforts to contain irregular migration in the Western and Central Mediterranean.This route entails travelling long distances in small boats with inapt engines. Shipwrecks are common, and engine problems or disorientation can leave people adrift for days or even weeks, probably making this route the most dangerous way to Europe, with 4016 lives lost during 2021 alone, over twice as many than the previous year.After landing, a different nightmare begins for the survivors. The Spanish Government implemented the so called “Plan Canarias”, aimed at keeping people on the islands whilst organising repatriations whenever possible. Several new camps have been built to host people on the islands. Asylum procedures have been delayed, with many waiting to apply for international protection even months after arriving. “Mañana” - tomorrow - resonates outside the reception centre of Las Raices, in Tenerife - it’s the Spanish word that everyone knows here, as it’s the answer they receive to everything.The feeling of being trapped and the uncertainty for the future cannot but exacerbate the trauma of what people had already to endure.

You can find this story in Al Jazeera English and Altreconomia.

FINDING HOME

Bosnia and Herzegovina 2021

A young man from Pakistan looks towards the border he has already tried to cross 13 times in Bihać, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Along the corridors of the abandoned buildings and in the shelters where the people on the move live in Bosnia and Herzegovina, time has frozen. Thousands of people try to reach Europe along the Balkan route every year. They are coming from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq or Syria, among other countries. They are fleeing wars and persecutions and looking for a dignified life.Young men represent the majority of those following this route, but there are many families with young children and elderly too. After the formal closure of the Balkan route in March 2016, people were left with no other choice than to pursue irregular ways of entry. Whilst originally most went through Serbia, the tightening of the borders along this route meant that since 2018, more people started to transit from Bosnia and Herzegovina instead.The country has become a forced stop for them. In fact, people regularly report being victims of pushbacks when they try to cross the border into Croatia, and thus into Europe, what is referred to as the "game". Money, phones and personal belongings are normally subtracted by the police or special forces involved. It is not uncommon to hear that people are deprived of their shoes too, thus having to walk back barefoot for hours until they reach their shelter, sometimes even in the unbearably cold Bosnian winter. Very often the pushbacks are violent and involve beatings and the use of dogs. Most people report trying several times, even dozens of times, before being able to reach a European country where they can apply for international protection.This means months, or even years, stuck in limbo, which cannot but exacerbate the trauma of what people had to endure. They come back, each time, to the same corridors, in a limbo where time is suspended.

You can find this story in Solomon. It was shortlisted at Siena Creative Photo Awards.FINDING HOME travelled around Italy as a solo exhibition commissioned by the Italian Consortium of Solidarity. It was also part of my wider solo exhibition on the Balkan route 'Along the border', commissioned by the Council of Ravenna for the Festival delle Culture.

Nisar Alì comes from Pakistan, here they call him the German, as he can speak this language. "Now is not the time for dreaming" he tells me. He first needs to reach Europe, get his papers and a job to help his family. Azizullah is a young man from Afghanistan. He has fled his country due to the Talibans. His dream is to reach Sweden and become a journalist, as one of those he could hear at the radio back home. Elena is a woman from Ukraine who lived for 20 years in the Netherlands, before being deported back. She is now following the Balkan route to reach the country she called home for so long, and dreams of writing a book with all what she has learned about migration during this journey. Mohamed used to work as a tailor back home in Afghanistan and he tells me that hopefully I'll take a good photo of him one day, when he'll have made himself a nice suit in Italy. Maha and Fadi are a Palestinian couple who were living in Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus, Syria. They just want to finally find a place where their children can be safe and go to school.

INVISIBLE BORDER

Greece 2019

Dimitri in a red dress, her favourite colour, to celebrate St. Dimitri's day. Her hands show her grace. Her eyes, the scars and the pride of her battle.

Dimitri proudly looking at the religious icons she had filled the wall of her bedroom with.

Dimitri was born in the small fishing village of Skála Sikaminéas, on the Greek island of Lesvos, and had to fight for her right to cross the invisible border of gender identity.Ever since telling her parents that she was a girl, at the age of fourteen, she struggled to be accepted. She faced difficult times, living in a mental institution during her childhood, as well as years of homelessness in Athens. After her parents passed away, she began wearing women's clothes and high heels.Dimitri told me that she finally felt comfortable with her identity and appearance. In the little sunny harbour of Skála, she used to walk with her head held high. The walls of her house were covered with religious images, as she was very devout. She loved opera, especially Maria Callas, and often played it loud, filling the calm air of Skála with melancholy.When I asked her why she often seemed sad, she said it was because of all the horrible things happening in the world, and she wasn't just referring to the news. There is in fact another story, hidden in the background, one of displacement. Another invisible border, the one between Turkey and Greece, lies in the waters off Skála Sikaminéas. Thousands of people risk their life to cross it every year, fleeing conflict, persecution or hardship, and many land on these very shores, which Dimitri could witness first-hand.

Invisible border won Portrait of Humanity 2021 and received an honorable mention in Photography 4 Humanity Global Prize 2020.It was featured in The Times, in CNN Style, and in the book Portrait of Humanity Vol 3 by Hoxton Mini Press. It was exhibited at PHOTO 2021 (Melbourne, Australia), Belfast Photo Festival 2021, and Indian Photo Festival 2021.Dimitri's story was also selected for the Pride Photo Exhibition 2023, starting in Amsterdam and travelling around the Netherlands for a year. It was then featured in BredaPhoto Festival 2025, as part of the Life Stories exhibition.

LIFE IN LIMBO

Malaysia 2019

Zhara and her neighbour Aquela making Mantu in their flat.

A small flat in a 15 storey building in the suburbs of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, has become home to Zhara, Malika and Hussain, three young siblings from Afghanistan. They are Hazaras and they had to flee their home country, where Hazara people are still facing ethnic and religious discrimination and persecution.In Kuala Lumpur, Hussain provides for his sisters by working in a bakery. He is the eldest. “You never know how strong you are, until being strong is the only choice you have.” These are his words on a social media profile. Malika, the youngest, is really good with languages and often acts as an interpreter from Farsi to English for the others. She teaches English in kindergarten, in the local community centre for Afghan refugees, to kids aged four to five. ‘They are cute, but also a bit naughty’, she says laughing. She has the most hilarious and sweet laugh. Zhara is a beautiful young woman, with a more composed personality than her sister. She cooks delicious Afghan dishes that remind her of home, as she is not very fond of the local cuisine. Zhara dreams of one day becoming a doctor.

Malaysia didn't sign the 1951 Refugee Convention and it doesn't recognise the refugee status. Yet there are 160 thousand registered refugees in the country, and many more unregistered. They are mostly Rohingya refugees who escaped from Myanmar, but other nationalities are present too - Syrians, Yemenis and Afghans amongst them.They aren’t allowed to work and cannot attend state schools, while the cost of private ones is too high for most of them to afford. They can only rely on UNHCR-issued ID cards. Under Malaysian law they are liable to arrest or deportation, but showing this card provides some protection. Since they aren’t allowed to work legally they have no choice but working off the books, with very low wages and no protection. What is worse, if the police find them working, they can be arrested or sometimes have to bribe them in exchange for turning a blind eye. It's a limbo similar to many asylum seekers awaiting a decision in Europe, the difference being, for them it will last until Malaysia changes its policy relating to refugees. The chance of relocation to a third country that could provide asylum is slim and the process can take years. The USA being the main country of resettlement from Malaysia, the chances have recently become even slimmer due the policies implemented by the Trump administration.This is Zhara, Malika, Hussain and many others’ everyday reality. Trapped between a painful past and a bleak future, far from home, they can only rely on their resilience.Names have been changed.

STOLEN MOMENTS

DEMONSTRATIONS

London, United Kingdom